A BRIEF HISTORY OF TEMESCAL VALLEY

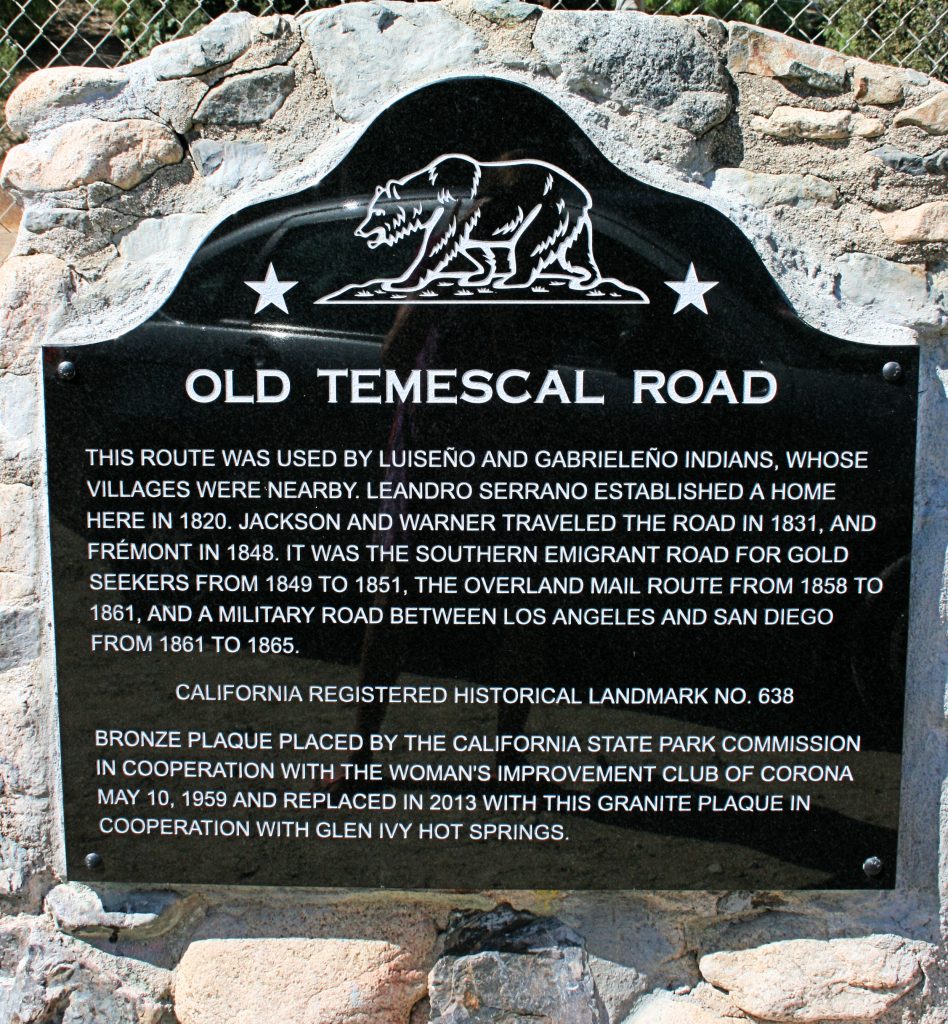

In 1818, a San Luis Rey Mission priest sent a soldier north to an area largely populated by Native Americans and grizzly bears. Leandro Serrano was told to befriend the indigenous people, who favored the area’s natural hot springs, and to eliminate the bears. He was given a “paper” – a permit or license to graze cattle on five leagues of land – roughly 34 square miles.

Serrano found the area abundant with flowing water and lush vegetation. He called the area Rancho Temescal and built an adobe in about 1824. That adobe was the first home built by a non-Native American in what would later become Riverside County.

Through the years, Serrano raised livestock, planted orchards and vineyards, married twice and fathered 13 children. As the family grew, Serrano built other adobes, as did his sons and sons-in-law.

Land barons and squatters arrived decades later, challenging Serrano’s claim. The U.S. Supreme Court in 1866, 14 years after Serrano’s death in 1852, denied the family’s ownership. The family was given 160 acres, but the court decision allowed others to file land claims and seek mining and water rights on property once considered to be owned by Serrano.

During the latter part of the 19th Century, Temescal was noted for its fabled tin mines, a stagecoach station for the Butterfield Overland Mail route along the Southern Emigrant Trail, the establishment of Temescal Sulphur Springs today known as Glen Ivy Hot Springs, the creation of the Temescal School District reputed to be the largest in the nation land-wise, the location of two U.S. post offices, and the place where Riverside County’s beekeeping industry began.

The Temescal Water Company, incorporated in 1889, purchased former Serrano land to provide water for a community later to become the city of Corona and its growing citrus industry. Pipelines diverted water from Temescal and Coldwater creeks, draining cienegas and springs, eventually leaving Temescal dry and desolate.

By the early 20th Century when historian Rose L. Ellerbe first referred to the area as “Temescal Valley,” clay mining was becoming the area’s leading industry. Residential growth was minimal until the mid-1980s when the first housing tracts were constructed, eliminating acre upon acre of citrus groves.

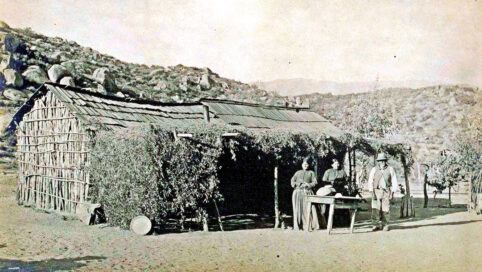

Temescal Valley Pechanga (Luiseno) home in 1900

WHO WE ARE

WHO WE ARE

_____________________

“The History of Temescal Valley” was written by Rose L. Ellerbe and published in 1920 by the University of California Press on behalf of the Historical Society of Southern California. Ellerbe, an accomplished writer, interviewed the two surviving Serrano daughters.

In 1861 the state’s first geological survey team spent several days in Temescal Valley. William H. Brewer kept a journal as the team checked out the Temescal Tin Mines and scaled Santiago Peak.

BREWER’S VISIT

TO TEMESCAL

COUNTY’S BEEKEEPING

BEGAN IN TEMESCAL VALLEY